Editor’s Note: Earlier this year, the Boettcher Foundation began a partnership with the Colorado Department of Education to support the Colorado Teacher of the Year Award. As the 2023-24 school year commences, it’s an opportune time to acknowledge the importance and impact that quality educators have in developing leaders and impacting communities.

One such career to highlight is that of Sharon Babb, a longtime Boulder Valley School District educator. Babb taught at Broomfield High School for 38 years and was a lifetime influence for thousands of students. She died on Sept. 9, 2020. One of her mentees is Curtis Esquibel, the Boettcher Foundation’s director of communications & community engagement. This is his tribute to an educator who changed his life.

It was Sept. 15, 2020, and I was engaging in a familiar pastime to pass some time – scrolling Facebook.

Sitting in my car as my son’s practice was about to end, I was enjoying a mundane moment of parenthood. That phrase, which had become a self-talk favorite whenever my self-worth felt reduced to being known as Sammy’s Uber driver, had actually felt elusive for months.

The pandemic had taken its toll on everyone, so it felt good to be in the somewhat familiar again with the activity of a new school year only a few weeks old.

Then, it flashed in front of me. A headshot of my beloved mentor and a note that read exactly as I feared — an obituary. Sharon Babb had died suddenly and unexpectedly.

My slouching posture straightened and then my eyes welled up in an instant.

Her celebration of life announcement described her as a longtime teacher, administrator, chorus director, and educator. Shaking my head in disbelief, I remember thinking how titles or roles rarely capture the essence of the leaders who shape us.

Instantly, my brain traveled backward to 1991 when, in Mrs. B’s Journalism 1 class, she led a unit on obituary writing. When I turned in a draft full of cliches and common phrases in describing someone, she told me how the printed obituary is often someone’s ultimate legacy, the last recorded words about their life and impact. “Start with words or an anecdote that bring a person to life. And never use something you’ve written or read before,” she said.

Well, here goes my attempt: Sharon Babb was an iconic force of humanity.

Mrs. B taught freshmen composition, AP English, served as my high school newspaper advisor, and would be the greatest educational influence of my life.

She was a gift to the wonder years, an irrepressible warrior for two things that remain timeless in their significance — literacy and caring.

I am proud to be one of her disciples — or Babblings, as we like to call ourselves.

It’s no secret there are hundreds (upon hundreds) of Broomfield High School alumni who belong to this legion. Mrs. B earned that following after molding young adults in the same building for 38 years. That’s 1964-2002 to be precise — yes, nearly four decades teaching multiple generations of community families in what today might feel like a dinosaurian epoch in education.

The week before the news of her death, a childhood buddy and I were reminiscing when, in 10th grade, Mrs. B would mistake him for his dad. She had taught his father two decades earlier in the same classroom. We would correct her initially when she would say the wrong name. But it became endearing over time – and she knew it humored us.

She always knew, despite her gravitas, how to lighten a moment.

Mrs. B was the educator we wanted to discuss historical literary works or current events with; she would help us to make sense of them, then challenge us to think critically and come to our own conclusions. “Keep asking why, and go deeper,” she would say.

She was a relic of a bygone era in some ways and cutting edge in others. In the early 1990s, she was the first person to tell and warn us about an approaching tech revolution that would disrupt every facet of society. She once had us write an essay about the positive and negative impacts of the “information superhighway.”

She expressed excitement about tech’s potential advances yet worried about its impacts on the arts and human relationships. Even then, she bemoaned the potential harm of thoughtless, rapid communication via electronic means.

In her classroom, she was old school. It mattered how you presented yourself (no baseball caps or hats of any kind were allowed) and how you greeted someone. If you didn’t contribute during one of her Socratic seminar discussions, she would call on you to discern why. She might have been gauging your preparation. Or lack thereof.

Regardless, you had to stay ready because you didn’t want to let her down.

Mrs. B’s extensive feedback, eye for detail, and what she demanded of us as learners were things of legend.

They were also daily reminders.

I recall writing many staff editorials for our student newspaper, The Eagle’s Cry, when she would instruct me to edit and re-edit incessantly, the practical execution of one of her favorite sayings: “writing is thinking; re- writing is writing.” Yet just when you start to obsess over word choice, she would land one of these gems: “Esquibel, stop writing to impress and instead focus on writing to express.”

Upon reflection, however, what I love most about Mrs B. was how she loathed labels and limits that students would put on themselves, or others. She would challenge us to expand our circles and not have our identities swallowed whole by the superficiality of teen cliques.

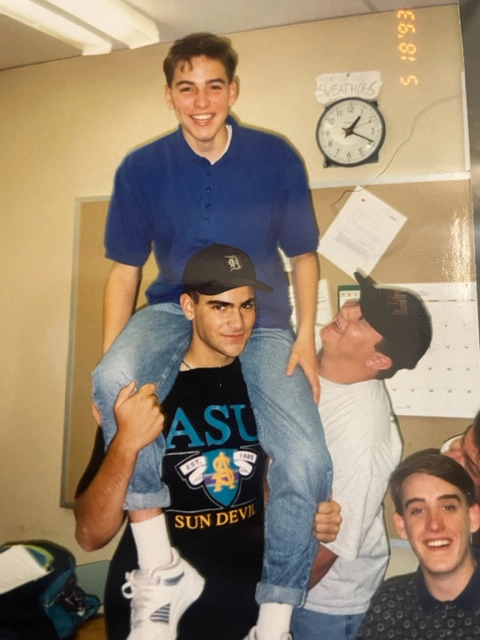

Our newspaper staff — a Breakfast Club-esque mix of colorful personalities from disparate social groups — always meshed under her leadership. Many of us would go on to become successful educators, writers, reporters, editors, even part of Pulitzer Prize winning teams.

Back then, we were a motley crew of suburban kids spending many evenings at the school putting the paper to bed.

Our windowless and cramped news lab was more of a basement dungeon than cub newsroom. It was a time when PageMaker ruled desktop publishing though our monitor screens couldn’t have been 10.” The layout process required deft, painstaking precision. In those days, we still used light tables, spray glue, and X-ACTO knives for page design.

There were many nights during our junior and senior years when our staff would emerge from our prideful chamber just in time to be home for the 10 p.m. news.

Mrs. B always would be right there with us, observing and coaching. In front of her would be a pile of papers to grade and a tiny black and white television with the volume turned just loud enough (and antenna stretched high) so she could catch that evening’s Jeopardy.

We would affectionately call her “Rain Woman” because she knew a lot about everything.

And then there were those pipes. She would sing, hum, and sound different melodies constantly, her brain always activating. Her voice and range were sounds to behold.

As teenagers, we had reverence for her because she wanted us to take ourselves seriously. There was something profoundly authentic in how she talked to us. We mattered and our opinions mattered.

And, most importantly, she never gave up on anyone.

Let me tell you a story.

At 15, I had a defining life moment with Mrs. B in that same Journalism I class. We were taking our fall semester final when I expressed frustration about exam questions not mentioned in the review material. As I muttered something petulant under my breath about fairness, she calmly said 20 words that I still recall verbatim 32 years later: “I’m stretching your thinking so that you apply the learning. That is always the test. It’s more than the exam that I care about.”

Of course I didn’t listen. I had studied long and hard for that exam, in part to impress her. So I doubled down in the way a punk teenager can do, this time audible enough for her to hear: “Well, it’s still BS.”

Now agitated, she told me to leave her classroom immediately. I stood up to walk out and, in the midst of an adolescent amygdala hijack, I crumpled up the test and left it on my desk.

That led her to drop this bomb as I exited her classroom: “An F is going to look terrible on your transcript.”

It was 7th period, the end of the day and our last day of school before the holiday break. I wandered the halls for the next half hour or so. After the bell rang, I was at my locker packing up to head home when I heard my name on the school intercom—it was Mrs. B’s voice—asking me to report to the main office. I was in trouble.

When I arrived to the main office, she calmly asked me to “please proceed in following” her back to her classroom. I remember the formality of her words and that subsequent walk of shame like it happened a few hours ago.

She closed the door to her classroom and for the next hour, we talked. She asked me questions, many of them out of curiosity and others with more of a purpose.

Then she delivered the ultimate hard-truth lecture about maturity, hard work, potential, and goal-setting. If you apply these things, she said, it will pave your way to excellence. And then she retrieved my crumpled exam, had me read the questions aloud, and tested me verbally on the spot.

I aced that final.

When we finished, and after I finally stopped apologizing for how I had acted earlier, she dropped this line: “There is no one else that I want to serve as the editor-in-chief of our newspaper in two years.”

Gulp. That was a role and opportunity I had never even thought about.

I went home, and maybe an hour or so later, our house phone rang. It was Mrs. B. She was checking in, and told me to have a great holiday break. “Come back in January ready to achieve. And be forewarned, because I am going to push you,” she said.

I did come back ready and she pushed me all right. She pushed all of us. Hard. I would go on to be the editor- in-chief of The Eagle’s Cry – and we would win multiple awards for our news and editorial writing over the next several years.

Mrs. B also would attend many of my high school basketball games, sitting in the far, upper corner of the bleachers, always by herself. An artist and writer, she was lukewarm to a sports-defined culture but she was an ardent fan of athletics and competition. Before every home game, I would look up to locate her in her corner spot.

I would be sure to extend a wave and she would exchange with a nod. And then she would bury herself in that pile of papers to grade.

But my crowning memory of Mrs. B has nothing to do with journalism or athletics. It was preparing to be in Thornton Wilder’s play, Our Town, with my classmates. It was a well-known BHS “secret” that Mrs. B would arrange an end-of-year play with her favorite AP English Literature classes—so it wasn’t an annual tradition. In those days, only seniors could take AP classes.

She so loved our 1994 senior class.

For the play, Mrs. B was the casting director. Many of us had never performed in live theater, including me. But there we were, memorizing lines and stage-prepping in the days leading up to graduation.

In addition to playing a major role, I compiled and designed the production program with Mrs. B as the final copy editor.

And somehow, we missed a crucial diction error and edit. We referenced “Miscellaneous Roles” as “Miscellaneous Rolls” in the printed program. Mortified when I found the error just minutes before the auditorium doors would open for showtime, I imagined the frustration Mrs. B would display upon seeing it.

I quickly summoned the nerve to bring it to her attention. And when I did, her face turned coral and her eyes grew big. Then with dramatic emphasis she blurted out her trademark phrase – “well savvy that?!” – before releasing an uncontrollable laugh.

As she collected herself a minute later, she leaned toward me in a private moment. Her eyes were clearly watering.

“That one is ours. We will always remember it.”

She was right.

Five years later, Mrs. B would be in Macky Auditorium at CU Boulder for my college graduation. I was presented with the Outstanding Senior Award from the School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

It was May 13, which also happened to be her 55th birthday – and she told me afterward that my award (which I didn’t tell her about) was the best surprise gift she could have received.

We would stay in close contact over the next few years. In fact, from the time I was in college and in the early years of my career, I would return to Broomfield High to talk to her students.

After nearly four decades of teaching, Mrs. B would retire in 2002 in part because of two events that she felt changed the nature of schools — Columbine and 9.11. Interestingly, I would cover both of those events as a professional journalist and they also forever altered my career outlook.

In my adult life, we would share these stories. Mrs. B became a friend, pen pal, and confidante. Every few years, I would receive one of her impeccably written notes.

Sometimes they were typed. Sometimes they were handwritten in her elegant cursive of an earlier era, in which she would lament the importance of writing by hand and its connection to thought formulation and expression. “I fear that students will suffer from a lack of continuous thought and the time to really consider what they are writing and its impact,” she wrote in the late 2000s.

She followed my career (as she did for so many of her former students) and would always remind me to take care of myself and keep perspective.

As for post-retirement life, Mrs. B dove headfirst into the business of educating adults about singing and performance through Sweet Adelines International. In her words, she was “fortunate to travel widely and meet people of every stripe.”

Just two weeks before her passing, my family and I were cleaning out our basement and I came across a Mrs. B note from 2011 and a letter of recommendation she wrote on my behalf in 1993.

I showed them to my wife and son, figuring it was about time to reach out to my mentor again.

In our last correspondence in 2018, she wrote about the importance of enjoying the “mundane moments of parenthood because the years will pass quickly. Life and its time compress themselves as we travel through it.”

Mrs. B closed her letter by telling me “You are and always have been very special to me. With a song for the future, Sharon.”

Ditto Mrs. B—and with many songs for the past, present, and future lives that you have touched and continue to impact through your students, who are now the teachers.

Curtis Esquibel is a 1994 graduate of Broomfield High School and former editor-in-chief of The Eagle’s Cry. An award-winning journalist and educator, Curtis serves as the director of communications & community engagement at the Boettcher Foundation. He still quotes Mrs. B often, both in his own head and when he’s connecting with foundation stakeholders.